The Prodigal Son: Luke 15:11-32

Among the many parables told by Jesus, the Parable of the Prodigal Son is arguably the most famous. A young man leaves his family, squanders his inheritance, and then returns home, where his father receives him with open arms. Fortunately for modern readers the language Jesus uses to tell the story is pretty straightforward, making it easy for everyone to understand the central themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Studying the Greek text, therefore, won’t radically transform our understanding of the parable, but it will enhance our understanding of the story, especially as we examine the words and actions of the three main characters.

Before the younger son embarks on his journey, he demands that his father give him his share of the family estate. The boldness of his request and the generosity of the father are underscored by the Greek term for “property” throughout the parable. Sometimes the word ousia (ουσια) is used (verses 12-13), while other times it is bios (βιος) (verses 12, 30). The former term, ousia, can denote property, but it more literally means “being” or “essence.” The latter term, bios, likewise refers to property, but it more literally means “life.” In both cases then, the son’s request for material possessions is, in effect, an attempt to sieze his father’s livelihood. By taking a portion of the family estate, the son is taking some of his father’s own life. And the father is generous enough to give that life to his son.

Unfortunately the son does not make good use of the “life” entrusted to him. He “squanders” it on a life of debauchery. The word for scattering here is diaskorpizo (διασκορπιζω), which more literally means “to scatter.” It can be used in multiple ways, such as squandering one’s wealth or dispersing a crowd of people, but it can also refer to a farmer who sows seed by scattering it in a field (as in Jesus’ Parable of the Talents in Matt 25:24). The imagery that Jesus is invoking, therefore, is of a young man who takes his inheritance and “scatters” it around like someone would toss seed onto the ground. The interesting contrast, however, is that whereas the farmer will eventually reap fruit from his scattering, this young man will reap nothing.

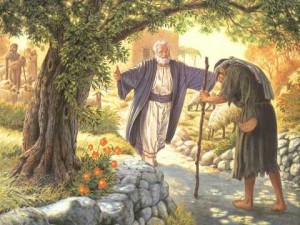

The young man eventually realizes he has reaped nothing and is on the verge of starvation, and he returns home to beg his father’s forgiveness. While he is still some ways off, his father catches sight of him and is “filled with compassion.” The verb here is splanchizomai (σπλαγχιζομαι), which is related to the word for a person’s inner organs: splancha (σπλαγχα). Such terminology sounds odd to us today, but it beautifully captures the visceral nature of the father’s reaction. His compassion for his son runs more than skin deep; it penetrates into his innermost being. It’s also interesting to note that this verb for compassion is most often used for Jesus. The father thus feels a deep, internal compassion for his son in the same way Christ does for us.

The father receives his youngest son back with unconditional love, but the older son is less hospitable. Frustrated by his father’s generosity, he thinks only about himself and his unrewarded obedience to his father: “All these years I served you, and not once did I disobey your orders, yet you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends.” In fact, he says that he has been “slaving away” (δουλοω) for his father all these years. The verb the older son uses here is the same term used for the work of a slave, and his word choice creates an interesting contrast between the two sons. The younger son has behaved recklessly but now wants to be treated like one of his father’s hired workers, whereas the older son behaved responsibly yet feels he is already treated like a slave in his father’s house. Both sons humble themselves in their speech to their father, but the older son’s comments smack of self-righteousness, exaggerating his devotion to his family by pretending to be a slave. He exudes a false humility, unlike his younger brother, who displays a true humility. Moreover, the older son’s words ring hollow, for he neglects to act like a slave in this very scene. The household servants kill the fatted calf and help their master celebrate the younger son’s return, but the older son remains outside and refuses to participate in the festivities. If he understood what servanthood truly meant, he would let got of his pride and join the family in receiving his brother home.

Learn more about practicing this method on your own.