1-2 Samuel

Synopsis

The books of 1 and 2 Samuel describe a nation at a crossroads. The Israelites have come a long way since their days of bondage in the land of Egypt, but they are struggling to form a new nation. Leadership has been a key problem. After the deaths of Moses and Joshua, the 12 tribes have been led by a series of judges who function as civic and military leaders. Often their leadership has proven sufficient, but the quality of that leadership has been fading with each new judge. By the time of 1 Samuel the Israelites have grown tired of this leadership structure and insist on having a king instead. God is not pleased with their request but ultimately grants their wish, and He directs the prophet Samuel to help with the transition.

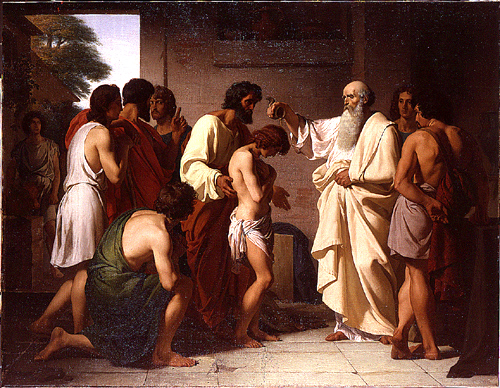

Samuel is one of the lesser known prophets of the bible but nonetheless a major figure. He becomes a prophet at an early age, serving at the temple in Shiloh under the care of the high priest Eli. He had been promised to the temple by his mother Hannah, who had been barren until the Lord answered her prayer to conceive a son. In return for God’s help, Hannah entrusts her son to the temple, where he grows up ministering to the Lord. One night the Lord appears to the young boy in a vision and declares that He will punish the corrupt house of Eli for not keeping His decrees. Soon afterward Eli’s family is destroyed, and Samuel takes on two significant roles: a prophet of the Lord and a judge ruling over the people.

Twenty years elapse, and an aging Saul appoints his sons to rule as judges in his place, but the Israelites reject them. They command Samuel to give them a king instead. Samuel feels hurt by their request since they are rejecting him and his family, but the Lord explains to him that it is really God whom they are rejecting since He is their only true king. God instructs the prophet Samuel to warn the people how corrupt a king will be, but they persist in their request, and God grants them what they desire. The period of the judges now comes to an end.

Saul becomes Israel’s first king, anointed by the prophet Samuel. He is an impressive ruler at first, standing head and shoulders above everyone else and leading the Israelites to victory against their enemies. He eventually loses the Lord’s favor, although his mistakes seem trivial compared to the crimes of future kings. Instead of waiting for Samuel to perform a sacrifice before the army goes into battle, Saul performs the sacrifice himself, even though he waited as long as he could before his soldiers started deserting. In another battle Saul neglects to destroy all the enemies and their livestock, as the laws on holy war require. Because of his disobedience, the Lord no longer approves of Saul as king, and He sends Samuel to the house of Jesse in Bethlehem to anoint Saul’s successor.

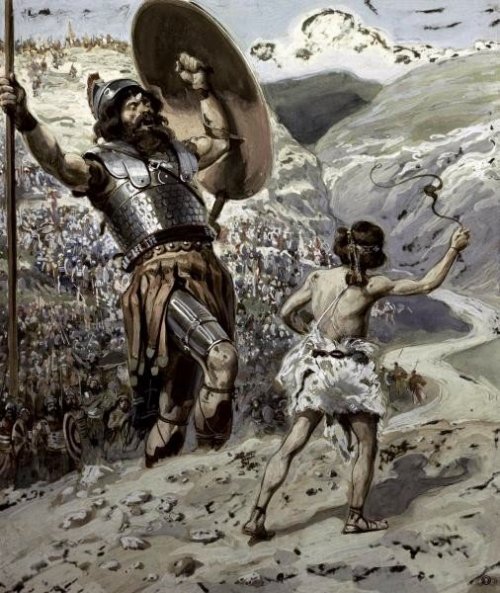

Samuel risks his life by anointing a new king while the current one is still alive, but he makes the trip anyway. When he arrives at Jesse’s house, he assumes the next king will be big and strong like Saul, but he can’t yet see what God has in store. As so often happens in the bible, God chooses the least likely candidate: a shepherd boy named David who is the youngest of eight sons. God’s favor is clearly upon him, and in the next chapter he fends off the giant Goliath, knocking him out with a slingshot and cutting off his head with the giant’s own sword. Reports of David’s exploits circulate widely, and as David continues to defeat the Philistines Saul grows jealous of David’s increasing fame. David had been serving in Saul’s court, playing the lyre for him and befriending his son Jonathan, but now Saul views him as a rival and wants him killed. David flees the royal city and becomes a fugitive for several weeks, nonetheless enjoying the support of soldiers loyal to him as well as many citizens he meets along the way. David eludes capture from Saul many times and even has a chance to kill Saul but refuses to harm the king. It is the Philistines instead who kill Saul and his sons in battle, paving the way for David to become the undisputed king over the 12 tribes of Israel.

David consolidates his reign by uniting the southern and northern portions of the kingdom, and he helps lead Israel to great heights politically and economically. The Lord makes a covenant with David, promising to establish a dynasty in his name, yet David becomes corrupted by power and commits transgressions even worse than his predecessor. While his army is away at war, David catches sight of a beautiful woman bathing near his palace and summons her to his bedchamber to have intercourse with her. Once he learns that she has become pregnant, he arranges to have her husband killed and takes her as his wife.

The child of the adulterous affair dies, but David goes on to have many children with multiple wives. When these children reach adulthood they become embroiled in bitter disputes, resulting in one being raped and another killed. The family discord becomes so great that one of David’s sons usurps the throne and forces David to flee again. Order is eventually restored but only after much bloodshed, and the once promising reign of David seems destined for failure. As the book of 2 Samuel draws to a close, David reaches his final days, and the people await announcement about who will become their next king.

Monarchy

Despite the difficulties of David’s reign, monarchy is now firmly established in Israel, and kings will appear throughout the rest of the Old Testament. However, the biblical authors never feel comfortable with kingship, and there are numerous reminders that the Israelites shouldn’t feel comfortable with kingship either. Even as the Israelites appeal to Samuel to crown a king for them, their rationale shows their foolishness. They’re dissatisfied with the way Samuel’s sons are ruling, so they ask for type of government based on dynastic succession, where the ruler’s son will take his place when he is gone.

Even more foolish is their demand for a king after Samuel explains how corrupt he’ll be. The king will press the people into service for him, making them fight his wars, manufacture his weapons for him, toil in his fields, work in his palace and wait on him hand and foot, and pay heavy taxes to finance his luxurious lifestyle and vast bureaucracy. As if this weren’t enough, Samuel adds the most dire prediction at the end: “You will become his slaves” (1 Samuel 8:10-18). Yet the people remain unfazed and insist this is what they want. They further add that they want to be like all the other nations around them since they have kings too, even though imitating the Gentiles is routinely condemned in the bible.

God of course was prepared for this request, and He had even prepared the people many years earlier for what a king might look like. Deuteronomy 17:14-20 outlines the rules for how a king may govern, although he won’t be like the kings of other countries. Like his counterparts from other nations he will have a cavalry to fight in battle, but it can’t be too big. In fact he can’t take credit for victory in battle since it is God who enables Israel to win. Like the kings of other nations he may marry multiple wives, but he can’t marry too many and form political alliances through marriage as Gentile kings do. Best of all, he can’t accumulate too much wealth! His main focus should instead be on God’s law, meditating on the statues of the Lord and observing them carefully so that he does not exalt himself over his fellow Israelites.

Needless to say, David does not live up to these standards, even though he got off to a good start. As the saying goes, absolute power corrupts absolutely, and David is no exception. Many of his descendants will be just as bad if not worse, fulfilling the dire warning that Samuel gave the people when they brought him this request.

Sacred Objects: The Ark of the Covenant & Casting Lots

Monarchy is the dominant theme in 1-2 Samuel, but other topics figure prominently as well. Some of these are sacred objects, like the ark of the covenant or lots used for discerning God’s will. Lots only appear a few times in Scripture and are never described in detail, so we have to rely on similar practices from nearby cultures to figure out what they looked like and how they were used. There were two lots, one black and one white, and they were called the “Urim” and the “Thummim.” These were small stones and may have been similar to the two onyx stones that were contained in the shoulder pieces of the high priest’s ephod (Exodus 28:9-10). Lots were used much like modern dice by being rolled on the ground to produce a result, but they were not used for games, and their results were not considered random. The Israelites used them when they wanted to figure out an answer to a question, and they assumed the answer came from God. The people would pose a yes-or-no question to God and then place the lots into a container, shake them, and then toss them onto the ground. (Imagine something like Yahtzee today.) The Urim and Thummim would correspond to yes and no answers, and casting them would show which one God favored.

In the bible lots are used to ascertain the identity of someone who has broken God’s commands (Joshua chap. 7, 1 Samuel chap. 14), to determine where God wants each of the twelve tribes to settle in the Promised Land (Num 26:55; Josh 14:1-2), and to figure out who God wants to serve as Israel’s first king (1 Samuel chap. 10). Rarely does someone use lots to determine something randomly, and only Gentiles use lots that way, as when Roman soldiers cast lots for Jesus’ cloak (Mark 15:24). Otherwise lots explain what God wants from His people. 1 Samuel isn’t very specific about how lots help the Israelites select a king, but it probably looked something like the following. The people ask God whether the king should come from such-and-such a tribe. For example, they could ask if the king should come from Manasseh. If the lots produced a no answer, they’d do the same thing for each tribe until a yes answer was produced. Then they’d arrange that tribe by clan and ask the same question for each clan until they got a yes answer, then the same for each household, and then for each person in the household until they finally settled on the one God wanted. This is how Saul was chosen.

Thankfully we know a bit more about the ark of the covenant. It’s a lot like the one featured in the Indiana Jones movie, except your face doesn’t melt if you open it. Plus we don’t know where it is. There are many legends about how the ark disappeared (it was relocated to Ethiopia, or hidden in a cave by Jeremiah, or buried under the rubble of the destroyed Temple in modern-day Jerusalem), but we will probably never find it. Thankfully the bible gives a detailed description of it.

First off, an ark is not a boat. The word for ark in Hebrew just means “box,” so the ark of the covenant (like Noah’s ark) is simply a wooden box. It’s about 4 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 2 feet high, plated in gold all around with two angel-like creatures called cherubim seated on top. No one is allowed to touch the ark (see the tragic story in 2 Samuel 6), so long poles are fastened to it so that it can be transported without touching the ark itself. Inside the ark are the two tablets of the ten commandments, and the ark acts as a vessel for this important record of God’s sacred covenant with the people. That’s why it’s called the ark of the covenant. One passage from the New Testament (Hebrews 9:4) suggests that a jar of manna and the staff of Aaron were also placed inside, but more likely these objects were placed next to the ark, not in it (see Exod 16:32-34).

In addition to preserving the ten commandments, the ark was also thought to be the place where God resided while the Israelites traveled from place to place. After wandering through the wilderness the Israelites brought the ark of the covenant with them as they crossed the Jordan River into the land of Canaan. They believed that God was somehow present to them this way, imagining God seated on top of the ark as if it were His throne. (In Numbers 10:35 Moses speaks to the ark as if God were present there.) God’s presence is especially important in battle, and the Israelites brought the ark of the covenant with them in war so God could help them defeat their enemies.

Regardless of what powers the ark possessed, it is interesting to think about how the mode of God’s presence continues to develop throughout the Old Testament. In the Book of Genesis God appears suddenly and often without warning, speaking to the patriarchs at random times but leaving them alone most of the time. In the Book of Exodus God speak to Moses on several occasions, always accompanied by great signs and wonders, as with the burning bush and the delivery of the ten commandments on Mount Sinai. Eventually the people build a tent where God can meet with Moses and the leaders of the community from time to time, making God’s appearances less sudden and sporadic. Now with the ark of the covenant, God will be present to the people more regularly, and He can accompany the people wherever they go. Eventually the people will place the ark in the Temple in Jerusalem, where God’s presence will be more permanent. But after the Temple is destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BC, it’s unclear what happened to the ark of the covenant. Hence the many legends about its fate.

Davidic Covenant

David shows a lot of interest in the ark of the covenant in 2 Samuel, even proposing to build a Temple so it can be housed permanently. Yet before David can draw up the plans for its construction, God sends a prophet to David and explains that something bigger is in store for the young king. Whereas Saul lost favor with the Lord, God promises never to remove His favor from David. In fact God forms a covenant with David, vowing that his throne will be firmly established and that God will be with David’s son and descendants to secure their kingship forever (2 Samuel 7:8-17). Thus begins the Davidic dynasty that will rule over the people for generations.

The covenant with David marks the fourth and final covenant of the Old Testament. (Jeremiah 31 speaks of a new covenant in the future, which is fulfilled by Jesus in the New Testament.) The first two covenants appear in Genesis, when God promises never to destroy the earth with a flood again (chap. 9) and when God promises to give Abraham many descendants and a land that they can call their own (Genesis 12-22). The third covenant is found in Exodus when God forges a relationship with the entire nation of Israel and gives them a set of commandments to obey. In each of these covenants, God makes an unwavering commitment to a person or group of people and offers them bountiful blessings, some of which are too great to believe. (Notice Abraham’s laughter at God’s promises in Genesis 17.)

In two of these covenants, the people are expected to do something in return for these blessings. The Israelites at Mount Sinai must keep God’s commandments, and Abraham and his male descendants must practice circumcision. But in the other two covenants, nothing is required of the recipients. Human beings will never be destroyed by a flood again, period. Even if they are wicked and continue sinning (and they will definitely continue sinning), God holds firm to His promise. He will never destroy them with a flood. Something similar happens with David in 2 Samuel. No matter how wicked David or his descendants might be, God will not remove them from the throne but still stand by their side throughout their kingship. David begins sinning just 4 chapters after this covenant is made, and future kings will commit many atrocities, yet God remains true to His word. He may punish the kings for their iniquities, but God will never remove them from the throne.

These four covenants reveal much about the nature of God as well as human beings. The terms of the covenants are carefully laid out by God, and it is up to us to uphold our end of the bargain, at least when there are conditions for us to meet. The unconditional covenants with Noah and David are easy for us to keep since we have no obligations! We should simply be grateful for the divine assurance of no more floods, and David and his heirs should be grateful to have their reign secured. In the case of the two conditional covenants, we know what God asks of us, and to receive the promised blessings, we need only to keep His commandments. It’s that simple.

As for the Lord, these covenants reveal a God willing to enter into intimate relationships with us and to limit His own power in the process. By committing Himself to the Davidic line or vowing not to send another flood, God takes several options off the table. He is not free to wipe us out again, no matter what we do, and He cannot choose another family to rule over Israel, or to even eliminate kinship for that matter. And for the conditional covenants, as long as we meet the requirements God lays out for us, God must give us the promised rewards. Otherwise God is not good or just. Even more surprising are the specific people and terms that God commits to in these covenants. To build a new nation that will worship only one Lord, God selects an old polytheist with an apparently barren wife. To give that people a more permanent form of government to guide them in the Promised Land, God chooses a shepherd boy and makes him king (despite God’s distaste for kingship), and He attached Himself to that man’s family even though he will break three of the ten commandments in one scene (2 Samuel 11), and his kids will be rebellious, conniving, and corruptible. Yet God loves us so much that He is willing to commit to us even as we fail Him time and again.

Recommended reading:

• 1 Samuel chap. 3

• 1 Samuel chaps. 7-10

• 1 Samuel chaps. 15-19

• 1 Samuel chap. 31

• 2 Samuel 2:1-7

• 2 Samuel chaps. 5-7

• 2 Samuel chaps. 11-13

• 2 Samuel 15:1-18

• 2 Samuel chap. 18

Reflection questions:

- Monarchy is a key theme in 1-2 Samuel, but these stories are really about government generally. What do we learn about government from reading 1-2 Samuel? With regard to particular leaders, Saul and David both begin as good leaders but soon go astray. What do their lives teach us about leadership?

- David is one of the most famous figures of the bible yet remains a complex figure. He performs heroic deeds yet sometimes behaves like a scoundrel. He slays enemies ruthlessly yet shows compassion on others, even those like Saul who want to kill him. He leads Israel to great economic and military might, yet he allows his kingdom to fall apart and even flees the throne. What does David’s complex character reveal about human nature, heroism, and mercy?

- When David commits adultery with Bathsheba, he is also guilty of coveting another man’s wife and killing the man to cover up his crime. But how guilty is Bathsheba for the affair? Did she have any say when the king summoned her to the palace, or did she have to comply since it’s dangerous to resist a king’s orders? Or is this something she wanted? Did she bathe in a public place in order to entice David? How does our own gender affect our interpretation of Bathsheba’s guilt or innocence?

- What do the relationships of many key figures in these stories teach us about friendship? Note the relationship of Samuel and Eli, then Samuel and Saul, then David and Jonathan, and finally Saul and David. (Note that their stories go beyond the passages listed above.)