A Catholic Approach to Scripture

Catholics have a reputation for not knowing the bible. Many of our Protestant brothers and sisters can quote the bible on command, even citing chapter and verse number. The average Catholic meanwhile knows the gospels fairly well and a few parts of the Old Testament, like stories about God creating the world or the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt. Other parts remain foreign to us though, and many of us are reluctant – even afraid – to read the rest of the Bible since so much of it comes across as strange or frightening. Why read apocalyptic texts like the Book of Revelation with its weird, symbolic predictions of the end of the world? Why waste our time on most of the Old Testament, where God is always angry and smiting people? Working our way through the bible can feel like walking through a mine field, avoiding the dangerous passages to get to the few good ones.

Well, they’re all good ones. Every passage in Scripture can be rewarding to read, as long as you approach it properly. This website is meant to help you with that approach, providing several methods of biblical interpretation and various guides for meditative reading. You’ll learn to use specific tools to aid you in your study of the bible plus some forms of spiritual reading to enrich your prayer life. But before delving into specific texts and methods, let’s take a step back and see what’s unique about the way Catholics read Scripture.

Dual Authorship

If you were to ask the average Christian on the street what the bible is, they’d probably say “the Word of God.” They’d be right of course, but they’d only be half right. The Bible is the Word of God, but it’s also the words of human beings. That is to say, the bible contains God’s message to us written down by human beings in their own words. It’s not merely God’s Word copied down verbatim by the biblical authors, nor is it merely the thoughts and ideas of the human writers as they speculated what God intended. It is truly God’s Word, and it is truly our word.

This understanding of the bible has a long history in the Catholic Church but was most clearly expressed at Vatican Council II (1962-1965) in a document entitled Dei Verbum: “God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion” (§12) such that the bible contains “the words of God expressed in human language” (§13). This is more than saying that God used Hebrew or Aramaic to speak to the people at the time. God allowed the human authors to write in ways that made sense to them, to use their own unique writing styles, and to compose these texts like they would other types of ancient literature. They tell stories with talking animals and people who live to be 900 years old. They create colorful poems full of agricultural imagery, and they organize God’s commandments in a law code much like the Code of Hammurabi.

This interplay between God and humanity means that both are legitimate authors of the bible, not just God. Hence we have a dual authorship of Scripture, which again is emphasized in Dei Verbum:“God chose men and while employed by Him they made use of their powers and abilities, so that with Him acting in them and through them, they, as true authors, consigned to writing everything and only those things which He wanted” (§11). That’s a fancy way of saying that the human writers were not secretaries copying down God’s words as they heard them but chose their own ways of expressing the Word of God. The words of Scripture are at one and the same time the words of God and the words of humankind. God is thus the true author of the bible, but so too are the humans he used to communicate that Word.

This interplay between God and humanity means that both are legitimate authors of the bible, not just God. Hence we have a dual authorship of Scripture, which again is emphasized in Dei Verbum:“God chose men and while employed by Him they made use of their powers and abilities, so that with Him acting in them and through them, they, as true authors, consigned to writing everything and only those things which He wanted” (§11). That’s a fancy way of saying that the human writers were not secretaries copying down God’s words as they heard them but chose their own ways of expressing the Word of God. The words of Scripture are at one and the same time the words of God and the words of humankind. God is thus the true author of the bible, but so too are the humans he used to communicate that Word.

Many other Christians also believe in the dual authorship of Scripture, but not all. The most conservative and evangelical Christians oppose it, stressing only the divine authorship of the bible. You can see why they’d take this stance. Human beings are fallible creatures. We make mistakes, we get emotional, we have biases that skew our view of the world (intentionally or unintentionally). And yet, the Catholic Church proudly acknowledges that we played a role in the process of revelation. God showed a lot of faith in us by letting us choose how we wanted to spread His Word. When we read Scripture today, we should be grateful that we have played such a key role in God’s plan. At the same time, we must also be aware of the human aspects of these texts. Since they reflect the ways ancient people understood their world (e.g. people living ridiculously long lifespans, patriarchal claims about the inferiority of women), we’ll sometimes have to sift through these human elements to find the divine word lying beneath the surface. But be assured, the divine word is there.

The result is that God’s Word is communicated to human beings in a way that is intelligible to them, not in some esoteric script that only angels can comprehend. Only by speaking to us on our level can God communicate to us what He wants us to know.

Divine Inspiration

God and human beings thus worked collaboratively to bring the Word of God to humankind. This collaboration came about because God inspired the human authors of Scripture (2 Tim 3:16), but how did this happen? If human beings wrote things down in their own words – and human beings make mistakes – it seems risky for God to let us be part of this process. Well, God was willing to take those risks, as long as the most important parts of the bible remained unaffected. Dei Verbum puts it this way: “The books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation” (§11). Let’s unpack this statement.

The Bible is without error. That’s mostly true. The bible has some errors, like a primitive conception of the earth resting on giant pillars and having a dome in the sky. It also gets the names of kings wrong sometimes or has them reigning at the wrong time. But are these details really important? Many fundamentalists think so and work very hard to prove that these details are correct, but the Catholic Church considers this approach misguided. The bible is a sacred text conveying religious truth, so the only things that matter are those truths “for the sake of our salvation.” Human lifespans of 900+ years or minor mistakes about geography have no bearing on whether or not we’ll get into heaven. Religious truths like the 10 Commandments or Jesus rising from the dead – these things matter, and these are the things God insured would be accurately communicated to us. Hence God permitted humans to express these ideas in their own words and even make mistakes about minor things, but he guided them to insure the most important messages were conveyed properly.

The Bible is without error. That’s mostly true. The bible has some errors, like a primitive conception of the earth resting on giant pillars and having a dome in the sky. It also gets the names of kings wrong sometimes or has them reigning at the wrong time. But are these details really important? Many fundamentalists think so and work very hard to prove that these details are correct, but the Catholic Church considers this approach misguided. The bible is a sacred text conveying religious truth, so the only things that matter are those truths “for the sake of our salvation.” Human lifespans of 900+ years or minor mistakes about geography have no bearing on whether or not we’ll get into heaven. Religious truths like the 10 Commandments or Jesus rising from the dead – these things matter, and these are the things God insured would be accurately communicated to us. Hence God permitted humans to express these ideas in their own words and even make mistakes about minor things, but he guided them to insure the most important messages were conveyed properly.

But how did this happen? That’s a good question, yet the Church doesn’t get too specific in its answer. Somehow the Holy Spirit guided the human authors in their writing while still allowing them to choose their own words, writing styles, etc. Could the human writers feel the Holy Spirit working through them? Did God inspire only the religious parts of the bible but let the human authors express their own thoughts for the non-religious parts? Modern theologians grapple with these questions in different ways, but they quickly admit we’ll never know all the answers. Nor do we need to. As people of faith, we trust that God and the human authors worked together to give us God’s Word, even if a few of the minor details are a bit off. Again, it’s our salvation that truly matters, and God would never lead us astray there.

The Importance of Genre

Sacred Scripture is thus both fully divine (the Word of God) and fully human (the words of human beings). This second aspect presents a challenge to modern readers since these words come from human beings who lived centuries ago. Our ancient forebears were like us in many ways, but their customs, worldviews, and modes of expression were markedly different from our own. We’ll explore many of these differences in the Methods section, but for now let’s focus on a key concept for reading ancient texts: genre.

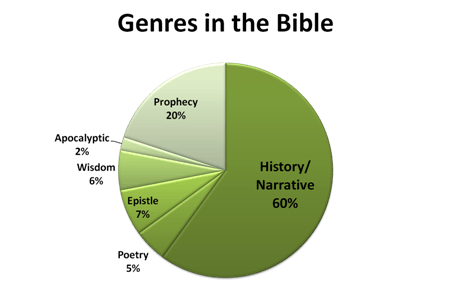

A genre is a “type” or “kind” of something. There are different genres of music (jazz, country, classical), movies (drama, romantic comedy, sci-fi), or even art (post-modern, folk, impressionist). The same is true of literature. Some books belong to the genre of fiction, some are biographies, and some might be cookbooks. In fact, many types of writings aren’t even books at all. We can talk about the genre of a newspaper article, a love letter, or the box score of a baseball game. Humans express themselves in a variety of ways, and our ancestors were no different. What is different is the kind of genres they used. They also wrote letters and biographies, but they had other types of writing as well, like creation myths, epic poems, oracles, legends, and memorial stelae. This happens in the bible too where we encounter a wide array of literary genres: laws, genealogies, songs, letters, historical narratives, sapiential literature, apocalyptic texts, and much more.

A genre is a “type” or “kind” of something. There are different genres of music (jazz, country, classical), movies (drama, romantic comedy, sci-fi), or even art (post-modern, folk, impressionist). The same is true of literature. Some books belong to the genre of fiction, some are biographies, and some might be cookbooks. In fact, many types of writings aren’t even books at all. We can talk about the genre of a newspaper article, a love letter, or the box score of a baseball game. Humans express themselves in a variety of ways, and our ancestors were no different. What is different is the kind of genres they used. They also wrote letters and biographies, but they had other types of writing as well, like creation myths, epic poems, oracles, legends, and memorial stelae. This happens in the bible too where we encounter a wide array of literary genres: laws, genealogies, songs, letters, historical narratives, sapiential literature, apocalyptic texts, and much more.

We don’t have space here to explain all of these genres, but let’s look at a few. There are two in particular which are problematic because they’re so different from modern types of writing: primeval history and apocalyptic literature. Both of these genres are written in narrative form and talk about the passage of time – the primeval history looks back to the past, whereas apocalyptic literature recounts visions of the future. When we come across stories about the past, we tend to read them as historical accounts, and when we read predictions about the future, we tend to dismiss them as crazy. Both approaches are harmful when reading these sections of the bible.

Stories from the Primeval History (Genesis chapters 1-11) are not historical in the way we understand the term today. They’re set in the distant past in a different type of world from our own, and they use figurative language to talk about the nature of God, the world, and humanity. The tale of Cain and Abel, for example, is not a historical record about a man who killed his brother many years ago but a creative story warning of the dangers of anger, jealousy, and succumbing to temptation.

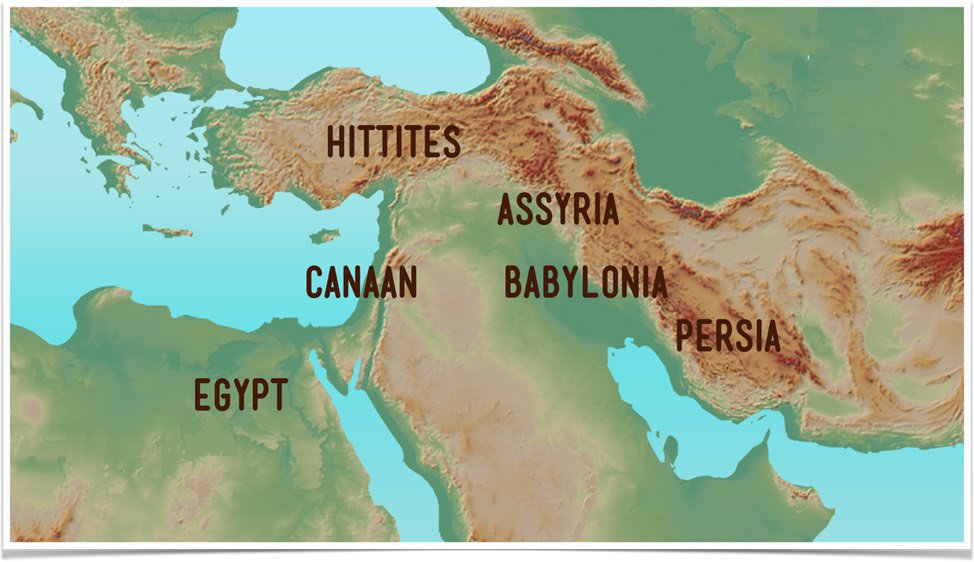

The primeval history of Genesis is not unique to the bible but resembles other texts from the ancient Near East. The Egyptians, Canaanites, and Babylonians all told stories about the origins of the world and humankind. They were typically set in the distant past with talking serpents and magical fruit granting mortality to anyone who eats it. They described how the gods destroyed the earth with a flood yet one man was saved by building a large boat and restored civilization after the floodwaters subsided. Their heroes lived to be thousands of years old and accomplished amazing feats we could only dream about today.

The primeval history of Genesis is not unique to the bible but resembles other texts from the ancient Near East. The Egyptians, Canaanites, and Babylonians all told stories about the origins of the world and humankind. They were typically set in the distant past with talking serpents and magical fruit granting mortality to anyone who eats it. They described how the gods destroyed the earth with a flood yet one man was saved by building a large boat and restored civilization after the floodwaters subsided. Their heroes lived to be thousands of years old and accomplished amazing feats we could only dream about today.

The biblical writers used this form of story-telling to communicate important truths about God, human nature, and our place in the world. When we read the opening chapters of Genesis then, we shouldn’t expect to learn valuable historical or scientific information explaining how the earth came about. That wasn’t the objective of the biblical authors, nor did any ancient civilization care about these sorts of things. Instead, the primeval history teaches us that the world is inherently good, we have a special place in the world because we are created in God’s image, and we are also prone to sin and temptation.

Once you get to Genesis chapter 12, the patriarchal narratives look a lot more like what we mean by history. But then you keep reading and eventually come to books like Daniel and Revelation that seem surreal. Few Catholics feel comfortable reading these texts since they’re often cited by over-zealous people trying to predict the end of the world. That’s not what they were meant for. Just like the primeval history, apocalyptic literature uses figurative language to communicate important theological truths. These books were written during times of intense persecution and therefore resort to symbolism to conceal their messages from their persecutors yet containing code that will be intelligible to their audiences. (Daniel was written in the 2nd century BC when the Greeks persecuted the Jews, and Revelation was written in the late 1st century or early 2nd century AD when the Romans persecuted the Christians.)

Many of the references to animals and beasts in these books are allusions to ancient empires who conquered Israel, like the Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans. Numbers are also symbolic. The number of the “elect” who will be saved is 144,000, which is not a literal total of those who will go to heaven but symbolizes the saving power of God. The nation of Israel consisted of 12 tribes, so the number 12 represents the totality of God’s people. If you square this number (12 x 12) and then multiply it by the number commonly used to express a large magnitude (1000), you get 144,000. This number in Revelation 7 and 14 thus represents the complete reversal of fortune for persecuted Christians and the boundless love of God. Many have died for their faith, but many, many, many more will experience the joy of heaven.

There are other genres in the bible as well, but these aren’t as difficult to comprehend. The New Testament contains 21 letters or “epistles,” and these are a lot like modern letters. One important thing to keep in mind is that most of these letters were written for a specific purpose and addressed to a specific audience, so they don’t always apply to all situations. For example, when Paul emphasizes the importance of faith and downplays the importance of works, he’s talking specifically about “works of the Law,” namely Old Testament laws like circumcision and kosher. He therefore wants the Galatians and the Romans to know that they don’t have to fulfill these old laws (Jesus changed all that), but he still expects them to do good deeds and live a virtuous life. Likewise it’s important to know the purpose of psalms. The word “psalm” is Greek for “song,” and these psalms were meant to be sung. That’s why many of our hymns in church are taken from the Book of Psalms. People sang these to praise and thank God (e.g. Psalm 92) and sometimes they used them to cry out to God in their despair and ask for His help (e.g. Psalm 70). We can do the same. Also, prophetic oracles occasionally predict the coming of a messiah to set things right, but their main function was to warn the people about sin and injustice and invite them to return to their covenant with God.

There are other genres in the bible as well, but these aren’t as difficult to comprehend. The New Testament contains 21 letters or “epistles,” and these are a lot like modern letters. One important thing to keep in mind is that most of these letters were written for a specific purpose and addressed to a specific audience, so they don’t always apply to all situations. For example, when Paul emphasizes the importance of faith and downplays the importance of works, he’s talking specifically about “works of the Law,” namely Old Testament laws like circumcision and kosher. He therefore wants the Galatians and the Romans to know that they don’t have to fulfill these old laws (Jesus changed all that), but he still expects them to do good deeds and live a virtuous life. Likewise it’s important to know the purpose of psalms. The word “psalm” is Greek for “song,” and these psalms were meant to be sung. That’s why many of our hymns in church are taken from the Book of Psalms. People sang these to praise and thank God (e.g. Psalm 92) and sometimes they used them to cry out to God in their despair and ask for His help (e.g. Psalm 70). We can do the same. Also, prophetic oracles occasionally predict the coming of a messiah to set things right, but their main function was to warn the people about sin and injustice and invite them to return to their covenant with God.

Moving Forward

Now that you’ve gotten a basic sense of how Catholics read the bible, please explore the rest of this site to learn more. The Methods page will be very useful as you probe more deeply into the sacred text. Obviously you’ll want to learn how God is speaking to you through the passages of Scripture, and these methods will help you identify the different ways that the human authors wrote and how to make sense of their writings. By doing that, you’ll be better able to hear God’s Word speak through them.

If you’d like to learn more about the topics covered above, check out some of the suggestions for further reading below. In the meantime, enjoy your visit to this site, and may your journey through the bible be a blessed one.

Further Reading

On a Catholic Approach to Scripture:

“The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church” by the Pontifical Biblical Commission (*note: a rich resource but nonetheless quite dense with much theological jargon)

Dei Verbum - decree issued at Vatican Council II that remains the most influential text for biblical interpretation today

On Genre:

Pope Pius XII, Divino Afflante Spiritu