Exodus

Synopsis

The Book of Exodus recounts the most central event in Israelite history. God’s people have become slaves to the most powerful nation on earth, and the Lord comes to their rescue and vanquishes their oppressors. The book actually gets its name from this event. “Exodus” means “going out” or “exit” and refers to the Israelites’ departure from Egypt.

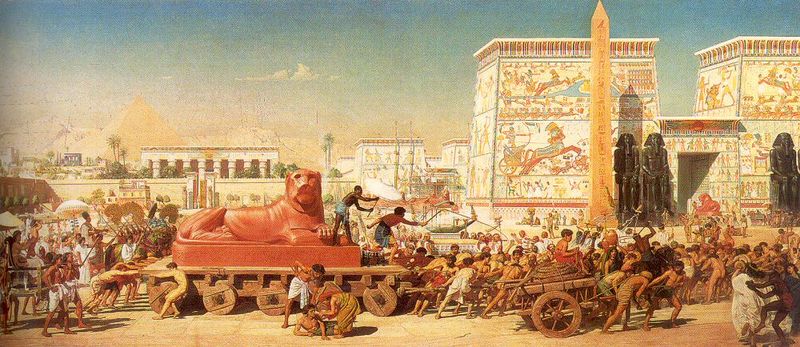

The Israelites had arrived in Egypt a few centuries earlier, forced to flee their homeland when famine struck the land of Canaan. Their fortune improved in Egypt with the help of their kinsman Joseph, and they grew numerous in the land. Worried that these foreigners would soon outnumber them and take control of their country, the Egyptians enslaved the Israelites, treating them more severely than any ancient people had ever treated slaves before. The Israelites cried out to God in their distress, and the Lord heard their plea.

God chooses an unlikely hero to save them. Although born a Hebrew, Moses was raised in the house of Pharaoh and thus part of the ruling elite oppressing his kinspeople. Eventually Moses turns his back on both the Hebrews and Egyptians and flees to the land of Midian where he becomes a lowly shepherd. One day while tending the flocks of his father-in-law, Moses encounters God in the form of a burning bush and is told to return to Egypt to liberate the Israelites. Moses is initially reluctant, yet God convinces him with many signs and wonders, giving Moses the courage to return to Egypt and confront the powerful Pharaoh. By the hand of Moses and his brother Aaron ten plagues devastate the Egyptian nation, but Pharaoh stubbornly refuses to release the Israelites until the angel of God massacres the firstborn sons of the Egyptians in a single night. After agreeing to let the Israelites go, Pharaoh quickly changes his mind and sends his army after the runaway slaves. Just as the Israelites approach the sea, God parts the waters for them, and the Israelites escape by crossing on dry land only moments before the waters collapse on the Egyptian army.

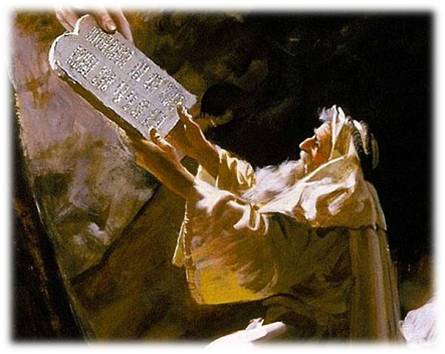

The Israelites journey through the wildness for several days and make their way to Mount Sinai, where God forms a new covenant with them. The ten commandments form the heart of this covenant, instructing the people to live holy lives by loving God and their neighbor. The Book of Exodus concludes with additional laws governing Israelite society and worship, and the former slaves begin the journey homeward, longing to return to the land that God had promised them.

Burning Bush (chapter 3)

The encounter between Moses and God at the burning bush marks a key turning point in the story. Not only does Moses transform from a Midianite shepherd into Israel’s savior, but the people’s understanding of God also evolves as He reveals His name to them for the first time.

This revelation occurs while God is paradoxically hiding. As Moses is tending his father-in-law’s sheep at the base of a mountain, he stumbles upon a bush that is burning but not consumed by the fire. This peculiar sight draws Moses’s attention, and suddenly the Lord calls out to him from the bush. In the ensuing conversation God informs Moses that He has heard the Israelites’ cries for help, and He directs Moses to lead the people out of Egypt. Moses is hesitant to up against the most powerful king on earth and he tries his best to get out of the situation, claiming that the Israelites won’t believe Moses is really sent by the Lord. So God gives Moses multiple miracles to perform to convince the people, and He even reveals His name so that the Israelites will know that this is truly their God.

This name, however, is mysterious. The Hebrew expression God uses in Exodus 3:14 appears below, but it is extremely difficult to translate. It’s most commonly rendered as “I am who am” or “I am who I am,” but it could be mean many other things. Strictly speaking, there is no verb tense in Hebrew, and readers often have to infer verb tense by the context of the verse. Present tense seems to be the best option, but others are possible. Perhaps God means, “I will be who I will be,” or “I was who I was.” Some scholars think a variant form of the verb is at work here, which would be equivalent to “I cause to be” or “I bring into being.”

Even after pinpointing the correct verb tense, the expression still seems cryptic. What does it mean to say, “I am who am?” Perhaps God means He is the one who exists, He is the ultimate Supreme Being or existence itself. This very philosophical interpretation was popular in the Middle Ages but doesn’t address the immediate situation of Moses and the enslaved Israelites. How would this idea of existence convince the people that this is the God of their ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob?

If God means, “I am who I am,” the interpretation is even more problematic. It’s almost as if God doesn’t want to give Moses an answer. Imagine if you asked someone today for their name, and they replied, “I am who I am.” Of course they are! Every person is who they are! But seriously, who are you? Names in the bible express the identity of a person, their essence, what makes them who they are (for example, Abraham means “father of a multitude”), and even to know someone’s name gives you a little power over them. This is why angels in the bible almost never reveal their name. So perhaps God doesn’t want to surrender His control but wants to remain a bit mysterious to Moses. “I am who I am,” and you’ll never know exactly who that is.

If the verb tense is meant to be future, then God’s power and mystery are even greater. “I will be who I will be,” and you’ll just have to wait and see! God can be whoever God wants to be, and that could even change over time. In His absolute sovereignty, God is free to be whoever God wants to be, or perhaps more accurately, free to act however God wants to act depending on the situation.

Still another possibility is that God wants Moses and the people to know that He has not abandoned them but is the same God as before. They are puzzled why God is silent and absent as they suffer in their slavery, but God is not indifferent to their plight. He is the God of their ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Exodus 3:6) and the God who created the world. God is “the one who causes to be,” recalling the opening chapters of Genesis when God created the heavens and the earth. God is even present to them now as they suffer at the hands of their Egyptian taskmasters. To say “I am” is very close in meaning to saying “I am here,” so God’s reply to Moses in Exodus 3:14 could have the connotation of presence. “I am here with you, people of Israel.” In fact, God said just two verses earlier that He will be with Moses as he confronts Pharaoh. This is a God who will not leave us orphaned but who is always present with us, even in our darkest hour.

Or perhaps God means all these things simultaneously, and the expression in Exodus 3:14 is left deliberately ambiguous in order to allow for all these possibilities. God is existence itself, and God is impossible to know fully, and God is free to act however He wishes, and God is the God of the past, and God is the God who is present to His people now. We can only speak in terms of possibilities since nothing is definite in this cryptic verse. Thus it appears Moses is back where he started. He doesn’t know exactly who God is, although now he is getting a fuller glimpse into the complexity of the divine. For the time being, he can address God by the name given in Exodus 3:14, and he can share that name with the people he is going to liberate. This name will be shortened to “Yahweh” over the course of the story, and it will be used for the God of the Israelites several thousand times in the Old Testament. Eventually Jews will decide that this holy name is too great to be uttered aloud, so they will render it by the Hebrew Adonai (“Lord”) out of respect for the Almighty. Modern translations of the bible often do the same, and so every time “Lord” appears in the text, it is actually a rendering of God’s name Yahweh. For that same reason Jews today omit the vowels from words like “God” (thus “G_d”) or “Lord” (thus “L_rd”) as a similar way to show reverence.

Thus it appears Moses is back where he started. He doesn’t know exactly who God is, although now he is getting a fuller glimpse into the complexity of the divine. For the time being, he can address God by the name given in Exodus 3:14, and he can share that name with the people he is going to liberate. This name will be shortened to “Yahweh” over the course of the story, and it will be used for the God of the Israelites several thousand times in the Old Testament. Eventually Jews will decide that this holy name is too great to be uttered aloud, so they will render it by the Hebrew Adonai (“Lord”) out of respect for the Almighty. Modern translations of the bible often do the same, and so every time “Lord” appears in the text, it is actually a rendering of God’s name Yahweh. For that same reason Jews today omit the vowels from words like “God” (thus “G_d”) or “Lord” (thus “L_rd”) as a similar way to show reverence.

Pharaoh vs. Yahweh

The great and awesome God who Moses meets at the burning bush will show even greater power in the subsequent chapters. Pharaoh has deluded himself into thinking his power is limitless and he can do whatever he wants to the Israelite slaves. He has no idea what their God is about to do to him.

The ten plagues and the drowning of the Egyptian army are famous even among people who don’t know the bible, but many readers of Exodus are bothered by God’s behavior, especially since He seems to be manipulating Pharaoh. Even if the Egyptians deserve to be punished for oppressing the Israelites, God seems to give them little choice, controlling Pharaoh’s actions so that he won’t let the Israelites go. As the plagues become increasingly severe, Pharaoh has second thoughts about holding the Israelites captive, but several times the text says that God “hardened Pharaoh’s heart” so that he wouldn’t let them leave (Exodus 4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17). Why would God prevent Pharaoh from releasing the Israelites if that’s the very reason He decided to intervene in the first place?

Some Christians are quick to criticize God in cases like this, dismissing the Old Testament God as cruel and vindictive and willing to abuse human beings just for the sport of it.

The God of the Old Testament, however, is often misunderstood, and a closer reading of the text as well as knowledge about ancient cultures yield a more positive interpretation. First of all, the Book of Exodus isn’t consistent about who hardens Pharaoh’s heart. Sometimes it’s God, but sometimes it’s Pharaoh hardening his own heart (Exodus 7:13-14, 22; 8:11, 15, 28; 9:7, 34-35), and in many of these latter examples it says that God predicted that Pharaoh would harden his heart. Scholars believe multiple writers composed the Book of Exodus, so it’s possible that one writer depicts Pharaoh being stubborn on his own accord and God foreseeing this stubbornness, and another writer included verses where God causes Pharaoh to be stubborn. It’s not clear why the second author would do this (perhaps it’s one of the reasons listed below), but the discrepancy illustrates that Exodus isn’t consistent about God hardening Pharaoh’s heart. Only one of the contributors to Exodus held this view.

Another factor to keep in mind is that the Old Testament authors viewed God as having supreme control over the world. Having created the heavens, the earth, and everything in them, God is all powerful and rules over everything He made. The bible sometimes goes so far as to say that God orchestrates everything, and nothing occurs in the world apart from God’s will. In Genesis 1, the sovereign Lord over all the earth created the world by putting order out of chaos, giving shape to the formless void and arranging the waters on the earth and above the earth as well as the sun, moon, and the stars, and creating everything systematically over the course of seven perfectly ordered days. Things were now as God intended. But the reverse is true in Exodus when God’s people live in a foreign land and become enslaved. So things must start over. God decides to undo creation by sending various plagues to ravage the land, resetting everything back to its original state of chaos so God can put things back together the way they are supposed to be. Since Pharaoh is a primary reason why things have gone awry, he is stripped of his power, relegated to the role of a pawn. God must fix the mess that humans have created, and He will take control over everything – even controlling Pharaoh’s heart – so that He can rectify what humans have ruined. After freeing Israel from the bondage of slavery and removing them from the land of Egypt, God’s plan can start over again. His chosen people will go back to the land He promised them, and they will continue their lives there as free people, not as slaves.

Other reasons for God’s behavior in Exodus have to do with ancient Egyptian culture. The Egyptians believed their kings transcended the human world and were semi-divine, mediating between the realm of the gods and the realm of humans. Some even believed the pharaoh to be divine while alive on earth, although officially that did not happen until after the pharaoh died. Either way, the battle between Yahweh and Pharaoh is not a contest between a god and a mortal – at least in Egyptian thought – but rather a struggle between two divine figures. Yahweh is more powerful than Pharaoh and will easily subdue him, proving to the Egyptians where real power lies. But more than that, Yahweh wants to prove that He alone is Lord over all the earth, and He has no rivals. Not only will Yahweh defeat Pharaoh, but He can even control his actions, hardening his heart so that Pharaoh will unwittingly help Yahweh carry out his own divine plan. Egypt’s “god” Pharaoh is reduced to a puppet whom the true God can manipulate as He pleases.

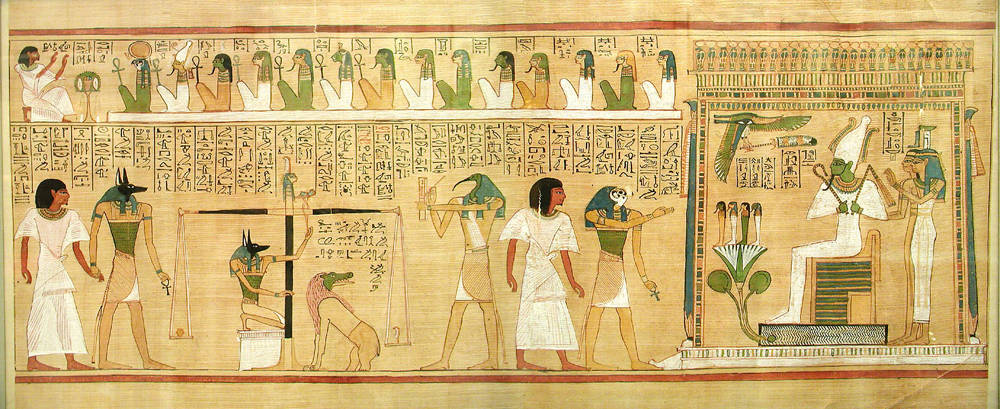

The Egyptian belief in the afterlife might be another factor in how Exodus depicts Pharaoh. The Egyptians believed that when a person died, their soul was led through the netherworld and brought to the god Osiris for judgment. To determine if the person deserved a good afterlife or a bad one, their heart was placed on a scale and weighed against a feather. If the person had lived a sinful life, their heart would be weighed down by sin and thus heavier than a feather, and Osiris would condemn their soul to a painful afterlife. But if their heart was pure, it would be lighter than a feather, and they would receive a joyful afterlife. Thus when the Book of Exodus says Pharaoh’s “heart” was hardened, it is using Egyptian imagery to say that Pharaoh is being judged for his crimes. Moreover, one of the Hebrew words for hardening is kabed, which can also mean to “make heavy.” So to say that Pharaoh’s heart is “hardened” is like saying that his heart is weighed down, meaning that Pharaoh deserves the terrible fate that God is giving him. Thus God’s “hardening Pharaoh’s heart” isn’t about Yahweh controlling Pharaoh but about God pronouncing judgment against Pharaoh and sending him to the fate he deserves.

Covenant

The Israelites’ escape from Egypt comprises the first half of the Book of Exodus. The second half is about the covenant God establishes with them at Mount Sinai. After escaping the Egyptian army, the Israelites wander through the wilderness, surviving on manna, quail, and water that God provides for them. Eventually they reach Mount Sinai, and God informs Moses that He is coming down to meet the people and they must make great preparations for His arrival. A dense cloud settles over the mountain top, and thunder and lighting streak across the sky. With the people trembling at the base of the mountain, Moses ascends to the top to learn what God now requires of them.

The ten commandments are well known, but they are not the only laws in this covenant. The remainder of the Book of Exodus lists hundreds of additional laws given to the people, and later books of the Pentateuch will include several more. Altogether the ancient rabbis counted 613 commandments for the people to obey. Obviously the first ten are the most important, but studying all the laws helps us understand what type of relationship God has in mind for us.

Sometimes God gives a law expressed apodictically, and sometimes it is expressed casuistically. An apodictic law is one that applies to all situations and all times. For example, “You shall not commit adultery.” There are no circumstances under which adultery would be allowed. It is completely prohibited. But other times God declares a law in casuistic form, meaning it should be considered case by case. An example occurs in Exodus 21 where an ox has hurt someone or something. If the ox kills another ox, the owner of the live ox must sell the animal and share the proceeds with the owner of the dead ox. But if the man knew his ox was reckless and likely to kill another animal, he has to give all the money to the other man. Or in another scenario, if the ox kills a human being, it poses a great risk to the community and must be put to death. But if the owner knew his ox was dangerous and might kill someone, then the owner and his ox are both put to death. To modern readers, these laws probably seem strange and outdated, but the difference between apodictic laws (true always and everywhere) and casuistic laws (depend on the circumstances) is important to keep in mind. Some things are non-negotiable for God and we have to obey them, but God also recognizes that life is often unpredictable, and all sorts of things can happen, so we need to make accommodations based on the situation.

All of the ten commandments are apodictic laws. Some of the other 603 laws are casuistic, and they’re usually easy to figure out since they begin with “If…” or “When…,” and then they present multiple scenarios. Understanding the ten commandments isn’t too difficult; oftentimes it’s following them that’s the hard part! They seem to place stringent limits on what we can and cannot do, often preventing us from doing things we would really like to do, at least sometimes. Perhaps a better way to look at them is that all ten commandments are about loving God and loving your neighbor. Take a look at the first three commandments (or if you’re going by the Jewish or Protestant numbering, they’re the first four). Each of these commandments is a different aspect of loving God. Worship only God, don’t misuse the Lord’s name, and keep the sabbath holy. The next seven commandments are about how we should love other people. Honor your parents, do not murder people, and so forth. You might recall that Jesus gives the twin commandment to love God and love our neighbor, but this same notion of loving God and neighbor is expressed in the ten commandments. These two ideas of loving God and neighbor permeate the entire bible. Thinking of the commandments in terms of love rather than obedience might make following them seem less burdensome. Rather than rigid rules we have to obey, they’re meant to be guidelines that enable us to love God and others more fully.

The later laws in Exodus have a lot do with how we should love God, namely how to worship him. The last few chapters offer elaborate details about how to build the ark of the covenant, the altar, and so forth. But the other laws in this part of Exodus are about interpersonal relations – in other words, how we should love our neighbor. Many of these laws and those that appear in the rest of the Pentateuch are about caring for the the poor, widows, orphans, and immigrants. Most of these groups are still marginalized today, and they were especially vulnerable in biblical times. According to God’s law, no one can be discarded since all are created in God’s image. In many Western countries, we not only look down at members of these groups but also strive to achieve as much wealth and prosperity as possible, even if it leaves many of these people behind. God frequently reminds us in Exodus and throughout the bible that no person can be ignored. Achieving prosperity is not a bad thing, but doing so is less important than caring for those who have little or nothing. And if you engage in business, that’s fine as well, but lending money to others in order to make interest off the loan is not allowed. In fact several texts say that after a certain number of years, all debts should be erased. (See the Jubilee Law in Leviticus chapter 25.) Such laws seem primitive by modern standards, but they have much to teach us. The Lord created this magnificent world for us to fill and multiply, and God marvels at all the amazing things we do and create. But no matter what, we must always love the Lord who created us and the people He put here with us. Nothing else is more important than this.

Recommended passages:

- 1:1-6:13

- 7:8-12:36

- chap. 14

- 16:4-17:7

- chap. 19

- 20:1-17

- chaps. 32-34

Reflection questions:

- Read the 10 commandments in Exodus 20:1-17. Notice how these commandments can be categorized as either a way to love God (commandments 1-3) or a way to love our neighbor (commandments 4-10). Consider Jesus' teaching that the greatest commandment is to love God wholeheartedly and to love your neighbor as yourself. How do the 10 commandments teach us what it means to love God and to love our neighbor?

- The commandments in Exodus chaps. 20-23 can be classified as either casuistic (case-by-case) or apodictic (applicable always and everywhere). Which laws are which type in these chapters, and what do they reveal about what God wants of us?

- God and Moses have a very interesting conversation in Exodus chap. 33 where Moses seeks to be God's friend. What does it mean to be friends with God, and what is revealed about the nature of human-divine friendship in this passage?

- God refers to Moses as a "god" in Exodus 7:1, describing how Moses will be a god to Pharaoh. What does this mean? How does Moses' mission affect his stature, and how does God share power with Moses in the Book of Exodus?

- In the golden calf incident in Exodus chap. 32, God's wrath is on full display, but what lessons is God trying to teach Moses here? God refers to the Israelites in a very peculiar way, calling them "your" people (referring to Moses). But throughout Exodus and the rest of the bible, they are always God's people. What is God trying to communicate to Moses here, especially since Moses was so reluctant to help the Israelites in chapters 4-5?

- The laws in chaps. 24-31 and 35-40 devote much attention to proper worship and sacrifice. Such laws seem obsolete and irrelevant to us today, but what do they reveal about how we should love God and how much effort and time we should put into that love?