New Testament

The New Testament contains four majors sections: the Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, Letters, and the Book of Revelation. Altogether these books tell the story of

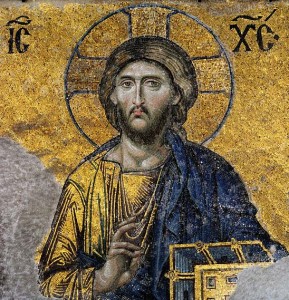

* The earthly ministry and teachings of Jesus

* The life of the early Church, and the work of the first missionaries

* The struggles that early Christians faced

Gospels

There are four gospels included in the New Testament canon. Why four? It’s hard to say for sure, but the process for their inclusion probably went something like this. Each of the gospels was written for a specific church or community, and they became increasingly popular over time. Soon other churches and communities began to read them as well, and eventually the early Christians had to decide what to include which texts to include in the bible and which ones to leave out. Since all four gospels had such widespread support and were read widely throughout the Christian world, they were all included.

Each gospel tells roughly the same story but has a different emphasis depending on which audience it was originally written for. The first three gospels are so similar that they are called

“synoptic,” which is Greek for “looks the same.” If you line up passages from Matthew, Mark, and Luke side by side, you can see how they’re virtually identical. (See the example below.) The theory behind how these similarities came about is complex, but scholars believe the shortest gospel (Mark) was written first, and then Matthew and Luke used Mark’s gospel to write their own, adding material they found from other sources.

The Gospel of Mark focuses on discipleship and the identity of Jesus. Jesus’ disciples leave everything to follow him and accomplish some pretty amazing things, like performing miracles and casting out demons (e.g. Mark 6:13). But they also make numerous mistakes and eventually abandon Jesus in his final hour. Mark’s gospel was probably written for an audience suffering intense persecution (see the many clues in chap. 13), and the evangelist chose to emphasize these things about Jesus’ original followers to show that they had struggles, too. And just as the original followers overcame their mistakes to preach the good news and spread Christianity to others, so also can Mark’s own readers do in their own day.

Mark also depicts Jesus as a secretive, suffering messiah. Jesus heals many people and casts out many demons, but he usually tells people to be quiet about these things. Jesus wants to keep his identity a secret for a couple of reasons. First, the word messiah means “anointed one,” and anyone associated with this title would be assumed a king. The Romans didn’t want people claiming to be king and they killed many who did, so Jesus prefers to keep this a secret until his ministry is near the end and he is ready to die. The second reason for the secrecy is that there were many contradictory opinions in Jesus’ day about what the messiah would be: a righteous ruler, a humble leader, a violent conqueror. Some Jews even expected two messiahs to appear. The word “messiah” carried too much baggage in the first century, and people would jump to all sorts of conclusions if Jesus embraced the term. So Jesus let people get to know him for who he really was rather than some label that would be misconstrued. Still let’s be clear; Jesus was the Messiah (or “Christ”), and Mark explains that fact in the opening verse of his gospel. He also adds a key component to Jesus’ identity: suffering. Jesus is the type of messiah who is tortured and killed, and no one can understand who Jesus truly is unless they see that suffering (like the centurion at the foot of the cross in Mark 15:39). And no one can know what true discipleship is either unless they’re willing to take up their cross and follow in Jesus’ footsteps.

The Gospel of Matthew borrows many of these same ideas from Mark but emphasizes other themes as well. One of the most noticeable features of this gospel is its focus on the Old Testament. Time and again Matthew illustrates how Jesus fulfills prophecies from the Old Testament, showing how Jesus is the long awaited messiah promised by God. This theme first perfectly with Matthew’s audience, many of whom were Jews and expected the messiah to come from the line of King David and fulfill the words of the prophets. However, Matthew doesn’t want to exclude Gentiles either, and there are multiple parts of this gospel that are directed at a Gentile audience as well, like the visit of the Persian Magi who pay homage to the baby Jesus. Most likely Matthew was writing for an early Christian community that had its roots in Judaism and many people who were formerly Jews, but there are also Gentiles who’ve become part of this church, and Matthew wants to show how Jesus appeals to both Jews and to Gentiles.

Matthew also depicts Jesus in a unique way for his readers. He agrees with Mark that Jesus is a secretive, suffering messiah, but he highlights a few other features as well. Jesus is descended from King David and is therefore portrayed with more royal imagery in this gospel (e.g. his genealogy in chap. 1 and the many kings in his lineage; the royal figure in the parable of the sheep and goats in chap. 25). Jesus is also a New Moses who redelivers the Law to the people, issuing his Sermon on the Mount in chaps. 5-7 like Moses decreeing the original Law in Exodus. Jesus is thereby the ultimate teacher and authority, instructing the people in righteousness so that they will live lives worthy of the kingdom of heaven.

The Gospel of Luke repeats many of the ideas found in the other gospels while adding its own unique perspective. Luke’s most dominant theme is how Jesus has come for all people, especially the poor and oppressed. In all four gospels, Jesus appeals to the downtrodden, the outcast, sinners, tax collectors, and similar groups, but the universal scope of Jesus’ ministry is clearest in Luke. Jesus speaks to more Gentiles, Samaritans, women, and other outsiders than in any other gospel, and he has more teachings on poverty and inclusivity as well. This is likely because Luke wrote for a mostly non-Jewish audience, and he wanted to show how Jesus unifies everyone into a single Christian family. Like Jesus, the Church welcomes all people, and we are all called to break down the barriers that separate us in order to become true disciples of Christ. By the same token, the image of Jesus that emerges in Luke’s gospel is one who embraces all peoples and who demands a radical restructuring of society so that no one is neglected or oppressed. Jesus has come to bring justice to an unjust world, and he will reverse the fortunes of those on earth, insuring that “the first shall be last, and the last shall be first.”

The Gospel of John is the most unique among the four gospels. Only a few stories from the other gospels are found in John, like the feeding of the 5000 and the crucifixion. Otherwise the remaining material is new: the wedding feast at Cana, the Bread of Life discourse, the raising of Lazarus, the story of doubting Thomas, just to name a few. The style of this gospel is also very different. Instead of parables, Jesus speaks in long sermons. Instead of casting out demons and healing numerous people, Jesus performs seven miracles or “signs” that prove his divinity. Instead of an infancy narrative, John’s gospel begins with a poetic prologue about Jesus as the eternal “Word.” Apparently John didn’t know the other evangelists but crafted his own story of Jesus in a brand new way.

John’s audience is also the hardest to pin down. They were likely undergoing great hardship and persecution, much like Mark’s readers, and the fourth gospel has numerous examples of dualism to illustrate the tensions they were facing: light vs. dark, spirit vs. flesh, Jesus and his disciples vs. the world. Probably John’s audience felt like outsiders compared to the rest of humanity, and this “us vs. them” mentality permeates the gospel.

It can also be seen in Jesus himself. Jesus allows for no middle way and will not tolerate lukewarm discipleship but insists on a radical abandonment of the values of this world and a complete surrender to the Gospel. Jesus is “the Way, the Truth, and the Life,” and no one can go to the Father except through him (John 14:6). Jesus also is more divine than in the other three gospels. While the three Synoptic Gospels all show Jesus’ divinity and humanity, John is much more focused on the former. Jesus does not weep at the Garden of Gethsemane, nor does he need Simon of Cyrene to help him carry his cross. Jesus is not a mere mortal but the great “I AM” (echoing Exodus 3:14), and he and the Father are one (John 10:30). Jesus is so close to the Father that they are one and the same, and this union with God is something we will enjoy as well (John 17:22).

Acts of the Apostles

The next section of the New Testament contains only one book: the Acts of the Apostles. Acts tells the story of the early Church after Jesus has risen into heaven. The book was written by the evangelist Luke and meant to be the second part in a two-volume narrative about Jesus and the disciples. The eleven apostles remain in Jerusalem after Jesus’ death and receive the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Emboldened by this experience, they preach the good news about Jesus to all who are willing to listen, and they strive to live just as Jesus called them to. They sell all their possessions and share everything with one another, celebrating the Eucharist and waiting for the return of Jesus at the end of time (which they expected any moment). Their zealous proclamation of the Gospel upsets the authorities, and many of them are imprisoned and even martyred.

One of their persecutors, Paul, has a vision of Christ on the way to Damascus and converts to Christianity. The second half of Acts now focuses on him and his numerous travels throughout the Mediterranean world as he brings the good news to the Gentiles. Various new churches spring up, and the issue of how Jews and Gentiles both fit in the same Church threatens to tear the Christian community apart. In a landmark decision by the church leaders at Jerusalem, they decree that Gentile converts to Christianity don’t need to observe Jewish laws like kosher or circumcision, paving the way for numerous people to enter the Church for decades (and centuries) to come.

Letters (“Epistles”)

The third major section of the New Testament consists of letters, or “epistles.” There are 21 such letters altogether, and they contain valuable information about the early Church as well as useful guidance for Christians today. Paul was responsible for many of these letters (at least 7), although sometimes the name of a famous leader of the Church was attached to a letter even though he didn’t write it (e.g. Peter or John). Most of these letters were addressed to churches to address problems they were facing as they tried to live out the Gospel, and others were written to specific individuals for guidance about similar matters.

The longest letters appear at the beginning of the collection. Romans, much like Galatians, explains the importance of faith for Christians and plays down the importance of the “works of the Law” (i.e. the Jewish laws from the Torah, such as kosher and circumcision). Romans also explains how God’s covenant with the Jews remains valid even after the coming of Christ, and yet both Jews and Gentiles fit perfectly into God’s plan of salvation for humankind. This same theme is picked up in Ephesians, which also gives advice on the proper structure of Christian households and subservience to Christ. 1-2 Corinthians are addressed to a community fractured by division and counsel them on how to be more unified. The notion that we are many parts yet all one body and that we all have different gifts coming from the same Holy Spirit can be found in these letters, as is a famous discourse on love (1 Corinthians 13). Philippians also stresses Christian unity, instructing readers to live with one heart and one mind, and it contains a famous hymn about the humility of Christ. The remaining letters in this section are fairly short with simple messages. Colossians emphasizes the exalted position that Christ enjoys in the universe, and it also warns against listening to false teachers and engaging in harmful practices. 1-2 Thessalonians exhort readers to stand firm in their faith despite persecution and to be ready for the second coming of Christ.

The next three epistles are known as the “Pastoral Letters.” They are written to individuals who were pastors in charge of Christian communities. Two are written to Timothy (1-2 Timothy) to warn against false teachings and practices and to set up rules for Christian ministers and priests. Titus reiterates many of these same themes.

Two other letters don’t belong in any of these subsections and are hard to classify. Philemon was written by Paul while he was in prison (as were several of his other letters) to encourage a man named Philemon to accept back his runaway slave Onesimus as a fellow brother. Hebrews is more of a sermon than a letter. It’s not addressed to anyone but emphasizes the exalted position of Christ in heaven, teaching that Jesus is the new high priest whose ultimate sacrifice eliminates any need for the sacrifices performed in the past. Hebrews also highlights numerous models of faith from Israel’s past, most notably Abraham.

The next 7 letters are called the “Catholic Epistles,” although this label can be misleading. They are catholic with a small “c,” and they can be found in all Christian bibles, including Protestant and Orthodox ones. They are catholic in the sense of being universal, addressing not just one community or pastor but the entire Church. James emphasizes the importance of doing good deed and not just believing in Christ through faith, and it also stresses care for the poor. The other six letters (1-2 Peter, 1-3 John, Jude) repeat many of the same themes: love, remaining steadfast in one’s faith despite persecution, and rejection of false teachers.

Revelation

The Book of Revelation is one of the strangest texts in all of Scripture. It is an apocalyptic book which uses figurative language to communicate important theological truths. Apocalyptic literature was written during times of intense persecution, so it resorts to symbolism to conceal messages from the community’s persecutors yet encodes them in such a way that the target audience will understand.

Many of the references to animals and beasts in this book are allusions to these oppressors, especially the Roman emperors Nero and Domitian. They will be overthrown, illustrating the ultimate triumph of good over evil – even if that victory is hard to see now. Numbers are also symbolic. The number of the “elect” who will be saved is 144,000, which is not a literal total of those who will go to heaven but symbolizes the saving power of God. The nation of Israel consisted of 12 tribes, so the number 12 represents the totality of God’s people. If you square this number (12 x 12) and then multiply it by the number commonly used to express a large magnitude (1000), you get 144,000.

The rich symbolism of Revelation explains how the present order is passing away and will be supplanted by a new one. The government and society are intolerant toward the Church, but Christians should not abandon their faith. The righteous must persist, and their reward in heaven will be great, while their oppressors will be tormented because of their wickedness. More importantly, the chaotic and terrifying life that Christians experience now is only temporary. They feel powerless now, but they must not surrender to temptation and immorality. Being Christian means being in conflict with secular culture and being critical of that culture. Only those who persevere to the end will find true happiness.

*To learn more about individual books, check out these online video summaries.

(Note: The linked videos are from the Bible Project site, which has a slight non-denominational Protestant bias but is still quite good.)

*To learn more about the People, Places, and Passages of the Bible, visit a scholarly resource here.